February 11, 2026

Revealed Emails Show Ken Starr’s Warm Ties With Jeffrey Epstein Despite Criminal Convictions

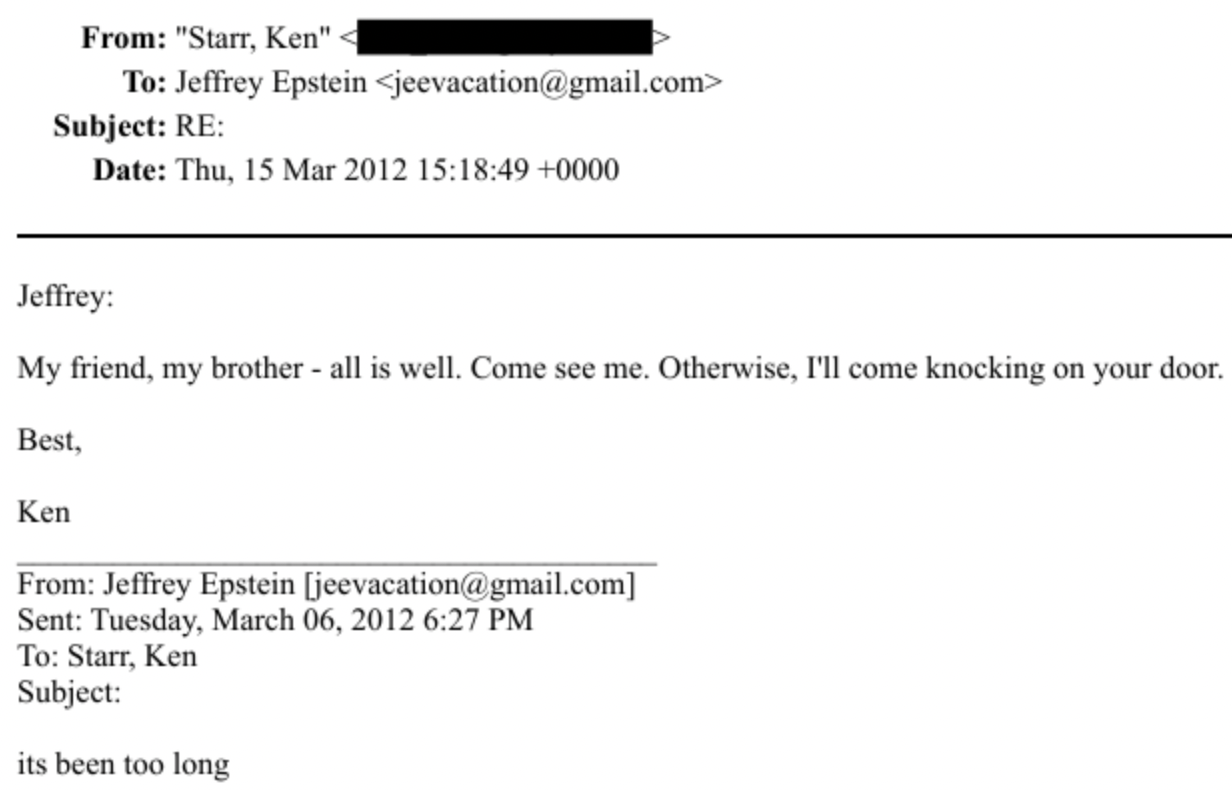

Ken Starr, known for his stringent prosecution during the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal, apparently did not maintain the same moral rigor when dealing with convicted child sex offender Jeffrey Epstein. Recently uncovered emails from the Department of Justice's latest Epstein files dump reveal that Starr, while president of Baylor University, personally hosted Epstein on campus in 2012, merely four years after Epstein had pleaded guilty to soliciting and procuring a minor for prostitution.

The correspondence between Starr and Epstein included not just professional niceties but extended to affectionate sign-offs with "hugs" and "love," striking a tone starkly contrasting the expected formalities between a university president and a registered sex offender. It wasn't just a one-off; Starr maintained this communication over years, discussing plans to visit Epstein in New York and Florida, and sharing updates on personal and current events.

These revelations come in light of Starr’s representation of Epstein during the latter’s 2008 plea deal negotiations, a time when Epstein managed to secure a lenient sentence despite heavy allegations. Julie K. Brown, the journalist instrumental in bringing Epstein’s crimes to broader attention, highlighted in her book, "Perversion of Justice," that Starr was a pivotal figure in Epstein’s legal strategy, employing a relentless legal campaign to keep him out of federal prison.

This ongoing association raises profound questions about the professional judgment exercised by Starr, considering his comprehensive knowledge about the severity of Epstein’s crimes. The relationship didn't merely blur the lines of professional conduct; it erased them, with Starr providing Epstein a veneer of respectability and access to high-profile networks, which, in retrospect, seems alarmingly misplaced.

Starr’s tenure as president of Baylor University ended controversially as well, with his departure following revelations that his office failed to adequately address allegations of sexual assault within the university, particularly involving the football team. Epstein himself surfaced in discussions about Starr’s frustrations with media coverage of the Baylor scandal, further intertwining their communications beyond mere legal representation.

The broader implications of such associations sketch a troubling landscape of power, privilege, and moral compromise. The coziness between Starr and Epstein, as evidenced in their correspondence, underscores a stark deviation from the ethical standards expected of those in positions of significant institutional authority. It also provokes a deeper reflection on the networks of influence and protection that individuals like Epstein cultivated to shield their criminal activities from full accountability.

As the legal and social reckoning with Epstein’s actions continues, the unearthed communications serve as a grim reminder of the complex interplay between power, justice, and accountability, questioning the integrity of those who chose to align with Epstein long after his criminal behaviors were publicly and judicially noted.